While negotiating the snow-mushy streets on the way to work, I found myself ruminating on what it’s like to write “good” characters, especially if one is only a fair-to-middling person oneself, morally.

It’s trendy right now to look at this from the reader’s point of view: to look at an author’s characters and guess at the moral makeup of the person writing them. Who does the story cast as the “best” character? What seems to make them “good” in the story’s viewpoint? Where does the gravity well of the story center itself? Do the morally-ambiguous or “bad” characters have more weight?

It’s worth asking questions like this to critique a story as a story; but I think the insights you can get about the author from them are limited. And who cares, really, unless you’ve got some torches and pitchforks sitting around begging to be used?

It’s an even trickier inquiry from a writer’s point of view. As humans, we generally don’t know what we don’t know. Our sense of ourselves as moral beings is its own benchmark. We recognize what we find morally repellent, but it’s much harder to identify what is morally superior to our point of view.

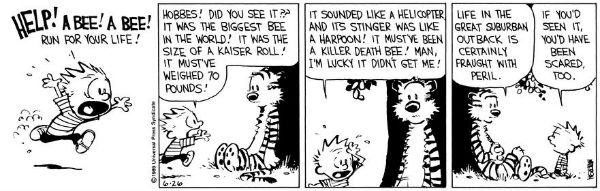

I got a sense of this once while writing fanwork about another author’s character. Inhabiting that character’s point of view, I was all set to write him as resentful and fretful against his superiors who were showing him compassion…when I realized abruptly that he wouldn’t do any such thing. He wouldn’t feel or act churlish in this situation: that was what I would do.

Getting schooled by a fictional character is an interesting experience.

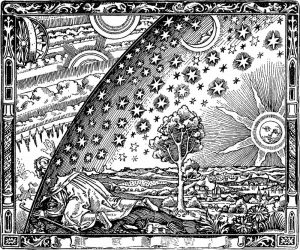

So when the characters are of your own invention, you have to try to get attuned to the harmonic overtones of your own moral knowledge, to sketch a dim sense of what you don’t already know. In a way, writing characters with a three-dimensional moral identity is as much hedging one’s bets as representing reality. It’s also why it almost never works to just have the story identify a character as “the good guy” whose viewpoint is upheld no matter what they do. A story should have a sense of some containing reality bigger than any one character, even (especially!) if the story operates through an unreliable narrator.

It seems weird to be talking about self-circumspection when we’ve got fascists and reactionaries stomping around using our own good faith against us. But good-faith circumspection is exactly what I recommend, both as writers and as readers. Nobody’s going to do our work for us. And we get to decide if we’re going to level up. But we don’t get to decide if other people will. It’s just as true in insane times as sane ones.

Or so I said to myself, as I was pulling into the office parking lot.