Happy Christmas Eve, everyone! I am enjoying the day off by eating a champion’s breakfast and perusing my list of blog topics saved during the Great Blog Hiatus.

To begin, a tweet from November 25:

Spoiler alert: the next tweet in the thread begins with the words “total bullshit.”

When I read this tweet a month ago, my reaction was mainly an indignant Now you tell me! But I’ve thought it over a little in the time since (a little, not a lot — it’s not like there’s nothing else going on), and aside from the sprinkling of salt, for me it still really comes down to a question of competing priorities.

As Long’s tweet thread suggests, the problem of word count is a bit more nuanced than the Hard and Fast Advice of the Internet would suggest. But although my decision to self-publish was precipitated by a piece of Hard and Fast Advice about wordcount, it wasn’t actually that difficult a decision. When it comes to selling your manuscript to a publisher vs. selling your book to the public, the question was and is: which set of upsides do you value more, and which set of problems would you rather have?

Traditional publishing upsides:

- In a word, cachet. You passed the gatekeepers! A Real Publisher published your Real Book!

- You don’t have to do every last bit of the marketing yourself.

- You also don’t have to do every last bit of the distro yourself.

- Project managers produce the book for you.

- You have access to professional editors as part of the deal.

- All of this equals a head start in making bank, and as a friend said when I demurred about this as an ambition: “No. Make fucking money. If it’s worth doing, it’s worth making money with.”

Reverse these, and you pretty much have the defining features of independent authorship. Whether those are downsides depends on your point of view. From my point of view, these are the upsides of independent publishing:

- “Project management” may not be a pair of words that an ADHD person likes to hear spoken together, but with that comes sweet, sweet control. To a publisher, you sell a manuscript. To the public, you sell a product: a product whose cover design you commissioned, whose layout you fashioned, and whose content you exerted your authority on. That’s worth a lot.

- Likewise, this product takes as long to produce as you decide it should take. You can arrange another editing pass (or not), choose the release date, set up your targets, and go. There’s no hurry-up-and-wait once you’ve finished the writing part.

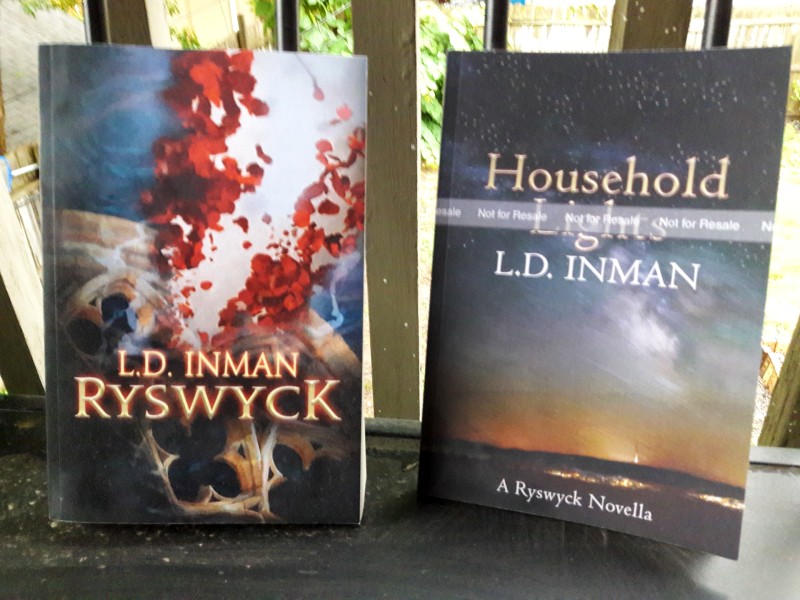

Like, I love Lois McMaster Bujold’s writing, but her books have had some god-awful cover art, which she was not responsible for and over which her control was very limited. When I imagined myself having as little say over what Ryswyck looked like, I thought: ughhh. It’s worth it to me to shell out some cash for a cover design that I like.

And that brings me to the downside of my chosen lot, which is: just as the control is all mine, the success of the product is all on me. In a traditional-publishing scenario, I would only have to sell the book to one agent. The agent then sells the book to a publishing house, and the publishing house sells it to the people. But in the modern environment, the author still has to do some of the marketing, they’re not going to clear that much overhead, and their name’s still on it, so people have to decide the book is good. Is there all that much difference, when all is said and done, between this and what I’m doing, selling the book person by person?

I admit, I am sometimes inclined to lament my bad karma when it comes to viral magic. I’ve known for years that my social media prowess is not destined to bring me cultic popularity — or even, let’s be real, a double-digit number of engagements per post. That’s not a vicissitude that an independent author likes to have on the list.

But I don’t suck at small-bore networking. I have friends who, when I ask nicely, have been happy to assist me out of their expertise, and not only that but to introduce me to their friends who have helped my project along. This is how I was able to purchase stellar cover art and launch a website with minimal outlay.

It’s true, Ryswyck is 248k words, a daunting prospect for the potential reader of an unknown indie author, designed (God help me) to turn the ratchet of tension by slow degrees at the beginning. Selling that to one agent might have been difficult, but selling it copy by copy to each individual reader is, let’s just say a heavy lift.

But though the return data is small, it suggests that if I get a reader to a certain early point in the book, they’re likely to really want to finish; and if they finish, they’ll have been highly rewarded. It’s a damn good book, it’s a damn good product, and I’m proud of it. More people should read it.

So, for a minute there, Long’s tweet thread made me wonder if I made the wrong decision. But all things considered…I don’t think I did after all.